It’s a Matter of Substance

|

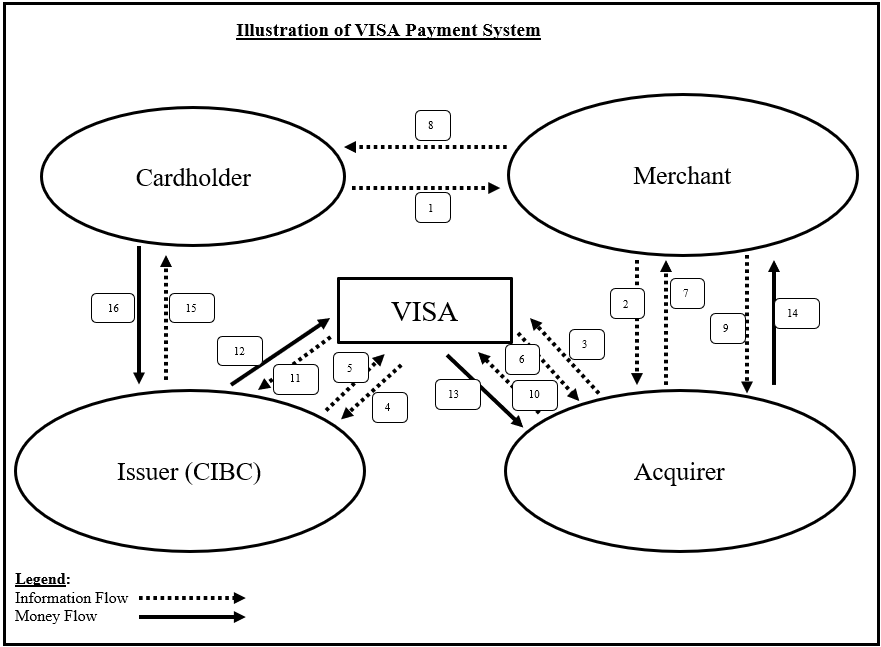

Services provided by credit card payment networks, such as VISA, Mastercard, and American Express, have long been regarded as taxable for GST/HST purposes. However, based on a recent decision by the Federal Court of Appeal (the “Court”) on an appeal by the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC), these services may now be exempt financial services. In the case of Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce v. The Queen,1 the service provided by VISA Canada (VISA) was found to be far too essential to the lending operations of its customer, CIBC, to be considered predominantly administrative. This decision overturns the verdict issued by the Tax Court of Canada (TCC),2 which had concluded that the service was taxable as an administrative service under the exclusion in paragraph (t) to the definition of a “financial service” under subsection 123(1) of the Excise Tax Act (ETA). This exclusion, a prescribed service, is further defined in section 4 of the Financial Services and Financial Institutions (GST/HST) Regulations (the “Regulations”). Overview VISA supplies CIBC with access to the VISA payment system, which allows holders of VISA cards issued by CIBC to instantaneously make purchases from participating merchants (e.g., retailers and service providers) worldwide. The service falls within the definition of a financial service under subsection 123(1) of the ETA. In the appeal, there was no dispute that the service in question was a single compound supply of several different components provided by VISA and little argument that the service fell within the inclusionary paragraphs of the definition. However, the Minister of National Revenue (the “Minister”) and CIBC disagreed on whether VISA’s service was excluded from the definition of a financial service under paragraph (t). Specifically, the outcome of the case hinged on whether the service in question was administrative in nature and, on this point, the Court disagreed with the findings of the lower court. Focusing on how VISA’s service was viewed by its customer, CIBC, and the end result of the supply, the Court found that the service was too critical to CIBC’s credit card business to merely be considered administrative in nature. VISA’s service provided CIBC with the ability to offer credit card services to its clients anywhere in the world, without the bank having to individually contact each merchant to authorize customer payment. The Court noted that it would be nearly impossible for CIBC to set up a similar system on its own as it does not have the relationships or global operations to do so. VISA also eliminated the need for CIBC to analyze the risk and solvency of each merchant that accepted its credit cards for goods and services purchased by cardholders. For these reasons, the Court found that VISA’s service went beyond that of an administrative service. _______________________________________________________________ Background CIBC’s contractual relationship with VISA provides it with the right to participate in the VISA payment system. This system is comprised of instruments, procedures, rules, and technology through which transactions are completed and information is shared among system participants. This system is what allows holders of VISA credit cards, whether customers of CIBC or other banks, to make purchases from participating merchants and immediately access credit granted by their financial institutions at the point of purchase. A diagram of how this complex system of transactions operates is provided in the appendix below. The major participants in this system are:

Essentially, when the cardholder presents a CIBC VISA credit card to a merchant for payment, an authorization request is sent electronically from the merchant to the acquirer. The acquirer sends this request to VISA, and from VISA, it is sent to CIBC. CIBC checks the cardholder’s available credit and returns either an approved or declined message to VISA, which is subsequently transmitted to the merchant. This process takes about one to two seconds from the merchant to CIBC and back using the VISA payment system. To settle amounts owed by CIBC to merchants, the various acquirers send transaction records daily to VISA, which are then segregated by lender, with the appropriate amounts owing forwarded to each bank. CIBC pays the amount, less its interchange fees, to VISA, which then sends the appropriate amounts to the acquirers, which in turn, pay the merchants. VISA sets the rules that each participant must follow to remain part of the VISA payment system. These rules are relatively static, and VISA regularly monitors compliance and acts where participants are not compliant. VISA also assumes a variety of risks under the arrangement, such as:

Despite the existence of the above-noted risks and an incredible volume, in practice, VISA’s actual risk exposure on transactions processed through its system is extremely low, with most of the risk being borne by the issuers and acquirers. _______________________________________________________________ VISA charged GST/HST on the supply of its service to CIBC, which led to CIBC subsequently filing rebate claims on the basis that it had paid tax in error. CIBC contended that VISA had provided an exempt financial service. The Minister denied the rebate claims, which resulted in the case being brought before the TCC. The appeal was denied on the basis that the service was “quintessentially administrative in nature.” CIBC then appealed to the Court, arguing that the lower court had committed reversible errors in arriving at the conclusion that the supply was an administrative service and finding that VISA was not a “person at risk.” Analysis As noted above, there was no dispute that VISA’s service falls under the inclusionary paragraphs (a), (i), and (l) of the definition of a financial service in subsection 123(1) of the ETA. Those paragraphs state:

However, a prescribed service is excluded from the definition of a financial service under paragraph (t) and section 4 of the Regulations. These provisions are the basis on which the TCC concluded that VISA’s service was taxable as an administrative service. Subsection 4(1) of the Regulations states: 4 (1) In this section, instrument means money, an account, a credit card voucher, a charge card voucher or a financial instrument; person at risk, in respect of an instrument in relation to which a service referred to in subsection (2) is provided, means a person who is financially at risk by virtue of the acquisition, ownership or issuance by that person of the instrument or by virtue of a guarantee, an acceptance or an indemnity in respect of the instrument, but does not include a person who becomes so at risk in the course of, and only by virtue of, authorizing a transaction, or supplying a clearing or settlement service, in respect of the instrument. (2) Subject to subsection (3), the following services, other than a service described in section 3, are prescribed for the purposes of paragraph (t) of the definition financial service in subsection 123(1) of the Act: … (b) any administrative service, including an administrative service in relation to the payment or receipt of dividends, interest, principal, claims, benefits or other amounts, other than solely the making of the payment or the taking of the receipt. (3) A service referred to in subsection (2) is not a prescribed service for the purposes of paragraph (t) of the definition financial service in subsection 123(1) of the Act where the service is supplied with respect to an instrument by (a) a person at risk, ... The Court found that the TCC did not have sufficient grounds to conclude that VISA’s service was predominantly an administrative service. In the Court’s view, the TCC made a “palpable and overriding error” when applying the term “administrative service” to the facts in this case and found that the TCC had described VISA’s service in two different and contradictory ways. On one hand, the TCC viewed VISA’s service as forming “an essential part of the ability for CIBC to offer credit card based services to their clients,” and giving “CIBC’s customers the ability to purchase goods and services anywhere in the world without CIBC having to individually contact each merchant to set up payment arrangements with them.” On the other hand, the TCC had also found that the service was simply cost saving and logistical simplification. Through the testimony of key executives at both CIBC and VISA, it was evident to the Court that VISA plays a key role in CIBC’s credit card business. CIBC’s vice president described VISA’s role as essential to “facilitating the ability of [CIBC’s] clients to purchase goods and services at merchants by enabling the transfer of money from [CIBC’s] clients to the merchant.” As testified by the head of CIBC’s credit card business, the indemnity provided by VISA is also considered critical to CIBC as it allows CIBC clients to make purchases worldwide without having to assess the risk of dealing with each merchant that accepts the VISA credit card or set up payment terms with those merchants. Because of VISA’s service being crucial to CIBC’s credit card operations, the Court simply could not view the service as predominantly administrative. In arriving at its decision, the TCC had relied heavily on a similar case, Great-West Life Assurance Company v. The Queen,4 in which the service of processing prescription drug benefit payments was considered taxable. The Court considered this decision but found that the situation was not entirely the same. In that case, Emergis Inc. (Emergis) received and adjudicated claims for benefits paid under drug plans provided to employees by customers of Great-West Life (GWL). Emergis arranged for payment of the drug benefits on a real-time basis, at the point of sale in pharmacies. However, Emergis did not have discretion as to whether claims should be paid—they simply followed the terms of the benefit plans and industry rules. As a result, the service was determined to be an administrative service because it provided a “cost saving and logistical simplification” to GWL. The primary benefit to GWL was that only one daily lump-sum payment was required to be made to Emergis, instead of individual payments to eligible claimants. In the case at hand, however, VISA’s service was found to change the substance of CIBC’s offerings for its clients as it was a critical element of the credit card services provided. Although there was minimal decision making involved in VISA’s payment network (the authorization by CIBC of the charge to the credit card is almost instantly provided at the point of sale), the Court found that the level of decision making should not be a determining factor when deciding whether a service is administrative, particularly when “VISA sets all the rules and maintains the decision-making authority over those rules under the VISA system.” _______________________________________________________________ Conclusion In the end, the Court decided to set aside the decision of the TCC and rule on the matter, rather than sending the case back to the lower court, on the basis that the TCC made a “reversible error by making contradictory and irreconcilable findings concerning the nature and impact” of the supply. The Court found that VISA provided an exempt financial service—one that was not excluded as an administrative service by paragraph (t) of the definition under section 123(1) of the ETA. Because the Court found VISA’s service to be an exempt financial service and not an administrative service, a “person at risk” analysis for the potential application of the definition of a prescribed service under paragraph 4(2)(b) of the Regulations was not required or undertaken in its decision. The Court’s decision makes sense as third parties providing administrative services are usually engaged for the cost saving and/or simplification benefits, which do not typically change the substance or nature of the transaction. In the GWL case, it was established by the Court that Emergis did not change the substance of the transactions. Emergis essentially operated within the confines of GWL’s existing business, and it did not augment GWL’s business offerings. If GWL could no longer use the service provided by Emergis, there would likely be a cost disadvantage to GWL, but its business would not be undermined. However, VISA’s service proved to be essential to CIBC’s credit card business. VISA’s withdrawal from CIBC’s credit card operations would likely cripple it or force it to find another service provider (e.g., Mastercard). Although CIBC has been in the consumer lending business for many years, the Court recognized that the attributes of a credit card are fundamentally different from that of other loans offered by financial institutions, such as a line of credit. Cardholders can conveniently make purchases at vendors worldwide, which is not available with other types of loans or credit facilities. Although the Minister argued that “a loan is a loan is a loan,” and a credit card is no different from other loans offered by CIBC, the Court rejected this argument, noting that it ignored the major advantage and functionality of credit cards over other types of loans. In its decision, the Court did not review the multiple potential supplies provided by VISA as the parties agreed at the outset that the service was a single supply with several indivisible components. If each of these components were treated as separate supplies, it might have led to a different outcome in this case. Implications This decision has many businesses asking: “What’s next?” It is undoubtedly a win for CIBC and other banks operating in Canada as GST/HST represents a cost to these organizations because of their inability to fully recover tax paid on goods and services which are inputs to their exempt activities. However, there’s also the question of tax paid in error by other financial institutions in similar situations and the flow-through impact of reduced net GST payable amounts on calculations by Selected Listed Financial Institutions under the Special Attribution Method to determine their liability for HST. As it stands, credit card payment networks, such as VISA, Mastercard, and American Express, are now considered to be providing exempt financial services. Unless there is a change to the legislation (the decision has not been appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada), these operators will no longer be able to simply claim input tax credits for any GST/HST paid on inputs to their credit card network activities and, as a result, they will experience higher operating costs in Canada. Will this mean higher fees to credit card issuers for using these services? Will interest and annual fees charged to the cardholders increase? How much of the additional cost will be passed on to participating merchants? In the end, it seems likely that cardholders will ultimately pay the price for the change in tax status resulting from this decision, unless the legislation is amended. Only time will tell.  Lisa McIntosh

Appendix

Source: Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce v. The Queen, 2018 TCC 109, para. 15. (CanLII), Schedule “A.” |